History of the Central Highlands of Tasmania

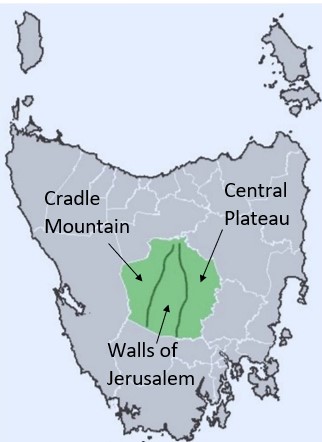

The mountains of The Central Highlands of Tasmania are divided into three distinct regions, Cradle Mountain, the Walls of Jerusalem and the Central Plateau. Both Cradle Mountain and the Central Plateau of Tasmania are very significant for me for several really good reasons. The Walls of Jerusalem are less significant because I never went there. You have to walk in and camp and that’s not something we did a lot of.

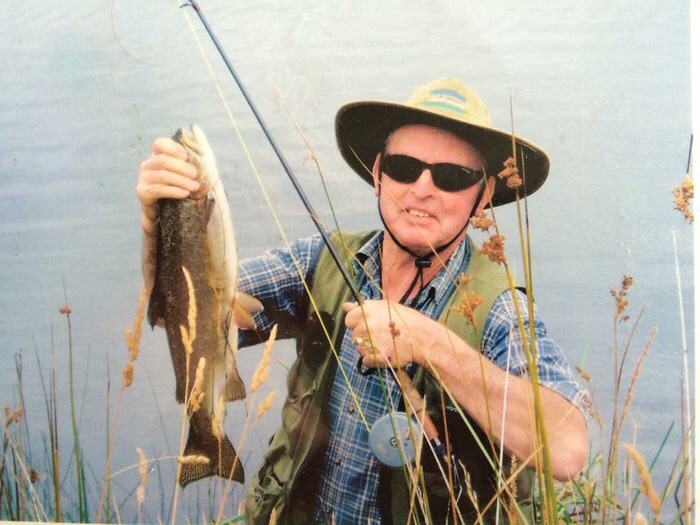

My dad worked for the Hydroelectric Commission, or the Hydro as we call it, early in his career setting up the infrastructure on the Central Plateau, that resulted in Tasmania being 100% powered by Hydroelectricity. My brother also completed his apprenticeship with the Hydro. We went fishing religiously and caught lots of big Trout in the lakes that power the Hydro.

I went bushwalking with my mother and sister at Cradle Mountain every week for quite awhile and I’m pretty sure we walked almost every single track in the Cradle Mountain World Heritage Area. It is our favourite place on this earth.

My sister also lived and worked at the Cradle Mountain Lodge and I was very jealous, because living and working amongst all that beauty would be so amazing.

My Great Great Great Grandfather James Magee shepherded sheep up into the Central Plateau during summer, which is called Transhumance. They do this because the fields down in the Midlands dry up, while the fields up in the Central Plateau are lush and green.

He would camp up there in a little stone and tin hut, while also catching possums and kangaroos for a side income. My father also did this on the farm in his youth, selling the meat and skin as pocket money.

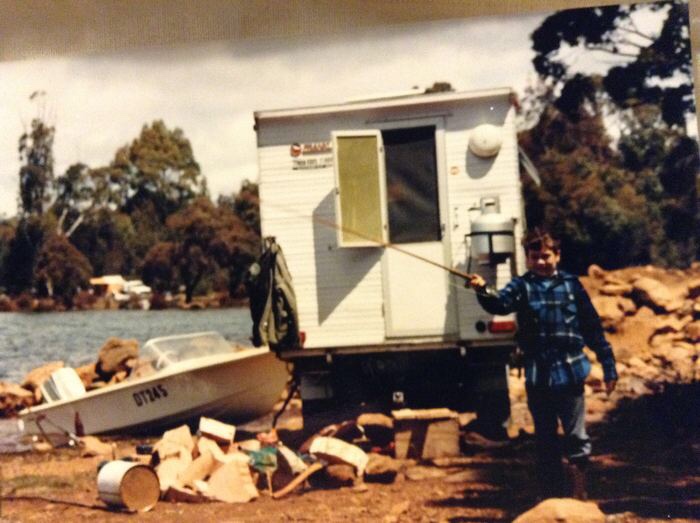

We would also sleep in a little tin hut when we went fishing up in the Central Plateau, it was on the back of dads Ute, i.e. a campervan. It was quite small and cramped, but much nicer than a tent when it’s snowing up the lakes!

Central Plateau History

The Luggermairrenerpairer clan are the traditional owners of the Central Highlands land and the area features many names inspired by them, including Miena, Liawenee and Waddamana. I pay my respects to their elders past and present.

The earliest known European exploration of the Central Plateau was Lieutenant Thomas Laycock. In 1807 a drought had descended on Tasmania and the Port Dalrymple settlement required extra supplies, so they sent Thomas on horseback bound for Hobart with dispatches for extra rations. He ascended to the Central Plateau via the Lake River to Woods Lake. It then took him eight days over the uncharted mountainous terrain of the Central Plateau, which would have been incredibly difficult for him, as its full of craggy towering peaks and deep valleys littered with volcanic boulders.

The marshland in between the peaks is notoriously boggy. He did really well just finding a pathway through the Central Plateau.

But at the same time it would have been so lovely to canter through the button grass plains, listening to the frogs croaking and the birds singing. Seeing the snow covered mountains all around him, as it can snow in the Central Plateau at any time of the year. He then followed the Clyde River to the Derwent River, which led him to Hobart.

There were many other adventurous folks that ventured up into the Central Highlands, probably even before Thomas Laycock, including Bushrangers who used the Central Highlands to hide from authorities. Predominately around the town of Bothwell, which provided them access to both the Central Plateau for hiding, and the main road for bush ranging.

High Country Trappers ventured into the Central Plateau looking for kangaroos, wallaby, and possums. The meat and skins would then be sold, and it was quite profitable for them, as the cold weather resulted in thick winter pelts that were highly sought after.

Tasmanian Tiger hunters also ventured up seeking payment under the bounty scheme. In 1830 farmers pooled their money to pay for Tiger skins. Then in 1888 the Tasmanian government introduced a 1£ bounty for a full-grown Tiger and 10 shillings for a juvenile. This was done as the Tigers attacked and killed sheep and cattle.

Thomas Toombs was a ticket-of-leave convict who ventured up into the Central Plateau, and first sighted the Great Lake in 1815, and he informed people of this adventure many years later. A ticket-of-leave was awarded to convicts for good behaviour, who were able to support themselves, but they had to stay in a specified district, so he may have strayed outside that district when he sighted the Great Lake.

All of these folk built Mountain Huts, using the materials they could find in the surrounding area, to live in while they went about their business. Many of these Mountain Huts still remain today, with the Du-Cane Hut being the oldest still standing. It was built by Paddy Hartnett, who was a hunter, bush farmer, and one of the first tourist operators, who began taking tour groups in 1910. As he started to take more people through, he built a series of huts along a track that is now the Overland Track, which is a six day hike along Tasmania’s most beautiful scenery from Cradle Mountain to Lake St Clair.

Building these huts started a proud tradition for Tasmania that continues today, although the shacks they are building these days are more like houses. In our younger days, my brother and I would go up Dooley’s Hill and we built many “huts” i.e. cubby houses.

Cradle Mountain

Cradle Mountain was originally called Ribbed Rock. However in 1827, the Van Dieman’s Land Company surveyor Joseph Fossey was searching for a land route between Surrey Hills, near Burnie and the Central Plateau, when he saw a dramatic mountain peak, which he immediately named Cradle Mountain because of the dipping profile between the main summit and Little Horn.

The area was then really opened up by Kate and Gustav Weindorfer, who shared a love of nature and met in Victoria in 1902.

Kate was a Tasmanian and they then spent their honeymoon on Mount Roland in 1906. Four years later Gustav and his friend Ronald Smith climbed to the top of Cradle Mountain, where Gustav was so taken by the beauty that he declared

‘This must be a national park for the people for all time. It is magnificent, and people must know about it and enjoy it’.

On their descent they selected the site for Waldheim Chalet and secured 200 acres of surrounding land to protect the area.

My first visit to Cradle Mountain was to Waldheim Chalet to play with the kangaroos and wombats that hang out there.

I then very much enjoyed bushwalking in Cradle Mountain with my mother and sister. It’s hard to pick a favourite walk. I loved walking around Crater Lake, up to Marion’s Lookout and on to Kitchen Hut.

The Ballroom Forrest is spectacular.

But climbing Cradle itself is the pinnacle, especially boulder jumping as you climb to the top.

John Beamont

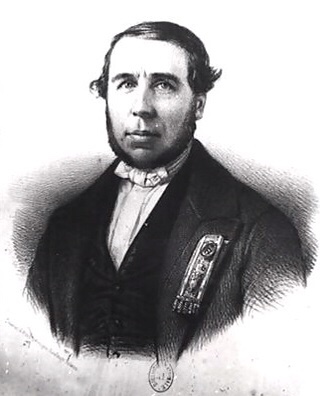

In 1817, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Davey, the Governor of Hobart Town, sent John Beamont to produce a map of the Central Highlands and discover new areas of pasture. He set out from Marsh (Melton Mowbray) journeying via Bothwell, Lake Sorell and Lake Crescent to discover the Great Lake, it’s the first officially recorded journey, however John lacked the surveyor knowledge to accurately record his journey.

He arrived at the Great Lake at Tods Corner and then ventured around to a bay where he found black swans and called it Swan Bay, where the town of Miena is now located. John must have greatly enjoyed his discovery, because when he passed away, he was buried in a lead coffin beside the lake and a memorial now stands there.

Travellers in this day and age, can find a shortcut to the North West Coast of Tasmania, where John Beamont set out from at Melton Mowbray, as it’s quicker to go through the Central Plateau than taking the main highway, especially if there are roadworks or it’s a busy day. Lets thank John for that shortcut.

After 1820, more settlers were arriving and had taken most of the good land. Which led to Assistant Surveyor Thomas Scott visiting in 1821 with a party of intending settlers, naming Lake Crescent and Lake Sorell. Of course they found the area already in use, with many Mountain Huts in the vicinity built by trappers, graziers, and bushrangers. Strayed stolen herds were also sighted and in 1863 a police station was established at the Steppes, with James Wilson appointed as Superintendent, due to his knowledge of stock and the lake country. James then moved into the small stone cottage that was built as the police residence and station. In 1874 James married Jessie Moyes and they had 11 children. From that first day in 1863, until 1975, there was always a Wilson living at the Steppes.

The Steppes was also an important rest paddock for shepherds on their journey up and down the mountains. Jessie worked as a postmistress for the postal service. James eradicated sheep scab in the flocks of neighbouring farmers. They hosted church services before a church was built in the area. Their daughter Mary established the first school in the Central Plateau. James and Mary volunteered for the Bureau of Meteorology taking weather readings. Jessie was a lover of birds and her daughters later promoted the area surrounding the Steppes as a wildlife sanctuary, which it became in 1930. Most importantly, James helped establish recreational fishing when he carried Trout fingerlings 38km to the Great Lake in Billy Cans. It was a point of pride that all fish survived the journey. The Wilson family left an incredible legacy for the Central Plateau of Tasmania.

Recreational Fishing

As previously mentioned, my father took my brother and I fishing up the lakes nearly every second week during fishing season. Lakes Crescent and Sorell, near the Steppes, were regular destinations. I can remember driving past The Steppes many times and feeling a special connection, without knowing why, but now I do. Because my great great great grandfather would have absolutely been friends with the Wilsons as he shepherded his sheep up into the Central Plateau. The Wilson’s were also key figures in establishing the worlds best Trout fishing destination. Thank you Wilsons.

There are also many more people I need to thank for helping establish recreational fishing in the Central Plateau. Salmon and Trout were introduced to Tasmania because the early settlers were disappointed with the Australian native freshwater fish, as they didn’t have the fighting qualities of the English Salmon. They deeply desired to introduce the Salmon, which is the most exciting sporting fish to catch. This resulted in Salmon Commissioners being appointed in 1861, to oversee the acclimatisation of Salmon into Tasmania. The Salmon Ponds were then built, with hatchery boxes and breeding ponds in the Plenty River, which is a tributary of the Derwent River, to mature the eggs received from England into fingerlings. It is one of the oldest continually operating hatcheries in the world.

James Arndell Youl transported the Trout and Salmon eggs to Van Dieman’s Land in 1864, which was not easy and there were many failed attempts over 12 years.

The Trout were an afterthought, with the eggs being a gift from Francis Buckland of Middlesex, a noted naturalist and angler author of the time. Thank you so much Francis.

James packed the eggs in moss, then kept them moist by melting ice. They were the first Salmon and Trout in the South Hemisphere, which were then developed into fingerlings at the Salmon Ponds. In 1870 they were released into lakes and rivers all around Tasmania. Salmon are anadromous, which means they hatch in fresh water, then migrate to the ocean, before returning to the fresh water to reproduce. It was thought that Salmon would do really well in the Derwent River, however the fish released into the Derwent only lasted a few years. The Trout however did really well and quickly built up to a breeding stock. They are now found in rivers and lakes all over Tasmania thanks to Francis.

Fly Fishing

Whilst Tasmania has the some of the best Trout fishing in the world, fly fishing is the pinnacle. In 1910 TB Simpson, who regularly fished the Great Lake, introduced dry fly fishing. Although the flies they bought from England weren’t very successful. Tasmanian Dick Wigram then came to the rescue, designing flies that were more suited to Tasmania and he published a book called Trout and Fly in Tasmania (1938) which is still widely used today.

Noel Jetson is another person to thank for all he did for Trout fishing in Tasmania. He was born on Flinders Island in 1933 and his family then moved to Tarraleah, where his love of fishing was born. He then started fly fishing with his work colleagues, when he was working as an engraver at The Examiner Newspaper. They would regularly explore the Western Lakes on foot, in Kombis and on their modified BSA Bantams.

Dick Wigram then came into The Examiner Newspaper one day with a bunch of Red Tag flies, which quickly became Noels favourite fly, as he caught many fish with them. Noel and Dick then became very good friends and Dick taught him to tie flies. Noel then spent a couple of years living in New Zealand with his wife Lois, before Tasmania lured them back, and they started the Jet-Fly fishing shop in Cressy in 1974. Through this business he became the first full time Trout guide in Tasmania, he also mentored many fly fisherman, taught fly tying at Launceston TAFE and was the first man inducted into the Tasmanian Anglers Hall of Fame in his own lifetime.

The Red Tag fly was easily our favourite fly too. It’s covered in black feathers with just a small dot of red to catch the fishes eye. It was generally the first one we tried every time we went fishing. My brother also started tying his own flies. That was so much fun. You put a tiny hook, in a tiny vice, then wrap around feathers and cotton to create your own little wonders, that you then use to catch big Trout!

Catching those big Trout via fly fishing is not easy, because the Flies are very light weight, which makes them very difficult to cast out onto the water. You therefore use a much heavier line and have to use a very specific casting technique, swinging your rod back and forth and back and forth, slowly feeding more line out, so you can get the fly out on the water. Learning this casting technique was not easy, not even slightly. But it felt so good to master it. Then once you mastered it, it was so much fun doing it.

With a dry fly that sat on top of the water like the Red Tag, you would need to sneak up to the water very carefully and quietly so you didn’t scare the fish. Then you would stand quietly and watch how the fish were feeding on the real fly’s, or how they were rising. Every time they rose, there would be a little splash as they ate the fly. Typically the fish would follow a pattern, rising in the same spot every time. The challenge was then to place your own fly in exactly the same spot, so it would rise and take your fly. That took a lot of practice and patience, but it felt so good to get it right.

London Lakes

Jason Garrett is another person I can thank for helping the Tasmanian Trout fisheries thrive by developing London Lakes, which is just over the hill from Bradys Lake. He purchased London Lakes in 1973 while working in Papua New Guinea surveying, prospecting, and fossicking. He then returned to Tasmania in 1978 to develop London Lakes. It is the only privately owned fishing lake in Tasmania and hosted the 8th World Fly Fishing championship in 1988, which was the first time it was held in Australia. Jason also represented Australia at the World Fly Fishing titles in the Czech Republic, US, Poland and Spain. His team won the Commonwealth Championship in Wales in 1990.

We never did fish at London Lakes, because there’s so many other lakes you can fish for free. However, Jason sold London Lakes in 2003 to a group of families from Sydney, who then refurbished the lodge. We did go and check it out then and geez they did a good job. It’s only a small Lodge but they’ve finished it off beautifully with stone and wood. They also run fishing tours and lessons.

Hydro Electric Commission

Tasmania’s 900 million ton annual rainfall provides a wonderful opportunity for hydroelectric power. Waterpower has been used throughout much of human history, initially as water wheels to grind grain, break ore and papermaking. Then in 1827 French engineer Benoit Fourneyron developed a turbine that could generate six horsepower. British, American and Austrian Engineers followed and the first hydro powered project was developed in Northumberland England in 1878 to power a single lamp.

The first hydroelectric power station in Tasmania followed close behind, with the Duck Reach Hydroelectric power station being built by the Launceston municipal council in 1895. It was the first publicly owned Hydroelectric power station in the Southern Hemisphere, operating continuously until 1955.

It was then James Gillies who really kickstarted hydroelectricity in Tasmania. He qualified as a Metallurgist in Sydney in the mid 1890’s. He then invented an electrolytic process capable of producing metallic zinc from mine tailings. The process was unsuccessfully trialed at Gillies Sulphide Concentrating Machine Ltd in Broken Hill, where he was working as a Manager. Then in 1907 he moved to Melbourne, where he patented his process and established a successful experimental facility. This gave him the confidence to propose a full scale works in Tasmania powered by Hydroelectricity, because the process was energy intensive, and hydroelectricity would provide cheap electricity.

James then started working with the University of Tasmania’s Professor of Mathematics and Physics, Alexander McAulay, who recommended using a hydroelectric system at the Great Lake, which Alexander had designed in 1905. The Tasmanian Government then gave James permission to do so in 1908 and he started the Tasmanian Hydro-Electric Power and Metallurgical Co. James and Alexander then worked closely together and construction began in 1910, with them building a small dam at Miena and the Waddamana Hydroelectric station in the Valley of the Ouse river.

Unfortunately design changes, adverse weather, company unrest, and a lack of capital, resulted in the company going broke in 1914. The Tasmanian government then bought the power company, opening the Hydro-Electric Department, which was Australia’s first public, statewide energy generating enterprise. It was backed by a thirty-year bulk power supply contract with Ballarat based Amalgamated Zinc, who had established a Zinc Works at Risdon on the Derwent river. The Waddamana Power Station was then opened at the Great Lake in 1916.

I worked just down the Derwent River from the Zinc Works early in my career and I would stare in wonder across the river at how the plant operated. In these times, it’s located in the Hobart suburb of Lutana. How many capital cities have a Zinc Works in the middle of suburbia!

James did establish a Carbide Works in 1917 at Electrona, which is south of Hobart in North West Bay. Here the limestone was reduced to lime, then roasted by coke to produce carbides, ferro alloys and carbon black products. Unfortunately, the government foreclosed on the Carbide Works in 1923. James then moved to Sydney where he continued innovating, producing patents for improved car lighting, soundproofing with diatomaceous earth and for a new type of refrigeration using dry ice. The Tasmanian government awarded him a state pension in 1935 for everything he did for Tasmania.

In 1929 the Hydro-Electric Department name was changed to the Hydro Electric Commission, or the HEC as we called it, and they were given far reaching powers to harness the states waterways. The HEC would then go on to enable Tasmania to be 100% powered by Hydroelectricity with 30 power stations and 54 major dams. An electricity cable was installed across Bass Strait in 2006 called Basslink, that provides excess power to the mainland.

Arthur’s Lake

The dams the Hydro Electric Commission built, also created the world’s best Trout fishing destinations. Our favourite fishing spot was Arthur’s Lake, which had been found in 1825 by the Assistant Surveyor in northern Van Dieman’s Land, John Helder Wedge, who was sent to find the source of the Lake River, which he found at Arthur’s Lake.

Arthur’s Lake originally consisted of the Blue Lake and the Sand Lake, with the Morass Marsh in between. The Upper Lake River was then dammed, which flooded the valley and created Arthur’s Lake. Water is pumped from Arthur’s Lake into the Great Lake, which then flows through the Poatina Power Station.

Arthur’s Lake was our favourite, because that’s where we caught the most fish! The Arthur’s Lake Trout also has a real pinkish flesh, which made them the most flavoursome Trout. Our favourite spots were Hydro Bay and Jonah Bay. Now whilst there were good roads around the lake, they didn’t actually extend to the lake or the camping grounds. The roads were constructed to easily access the infrastructure the Hydroelectric scheme had in place, not to make it easier for the fishermen. So to get to the camping grounds there were little tracks the fishermen had ‘created’ whilst driving to them. There was no construction involved, just people driving the same way all the time, which created tracks that other people followed. These were not good tracks, they were not easy to drive on, it was very slow going, as they were rutted and had many holes. When it rained they were even more treacherous as the land was very swampy and you were lucky not to get bogged. But the journey was worth it, as the campgrounds were right on the lake and you could see where the fish were feeding, or rising, as we called it, as they’d make a little splash when they ate the bugs. A couple of times we went even further around the lake and tumbled down to Tumbledown Creek. I swear it took longer to get around the lake than it did to get to the lake in the first place. But Tumbledown Creek has its own charms and it was nice to be in a new spot. To be fair, there were easier places to get to a campsite, but as you would expect, those tended to be overcrowded and not close to the best fishing spots.

When they dammed the Upper Lake River and flooded the valley to create Arthur’s Lake, they didn’t cut down the trees beforehand and the all the trees died. So all around the lakes shores are forests of dead trees, which can be quite pretty. The fish loved these trees, because there was plenty of bait for them to feed on. So it was also a great place to fish! But it was also so easy to snag your lure on the trees.

Hydro Villages

The HEC found that access to the Waddamana power station was difficult, because it was in such a remote location and there was a lack of roads to get workers on site i.e. there was only a horse drawn wooden tramway. So they started building housing on-site for workers in 1915, to attract and retain employees in the construction phase. It started as canvas tents and primitive single men’s quarters, then improved to demountable buildings that were moved between villages as required. The houses on site were initially only for senior staff, until 1940 when all employees gained access. At Tickleberry flats in Tarraleah, married staff were given timber to build there own accommodation, so that partners could join them in the remote locations.

Many Hydro villages were then built in some of the most remote areas of Tasmania and my Dad lived in most of them during his career. I received great pleasure as he drove us through them, explaining where he lived, and what he got up to.

Bronte Park

Bronte Park is a Hydro village in the Central Plateau of Tasmania, just 3km away from the geographic centre of Tasmania. It was built in the 1940s to house workers building the Tungatinah and Nive River schemes. By the 1950s, 700 workers lived there with a store, police station, post office, school, cinema, hospital, dairy and a church. David and Robin Wiss then purchased Bronte Park from the Hydro Electric Commission in 1991, after they had been leasing it since 1978.

We would drive through Bronte Park regularly to get to Bradys Lake, where our neighbours the Meaghers owned a shack, which they kindly allowed us to use. We would also regularly have dinner at the Bronte Park Chalet, while listening to all the locals having a raucous chat.

Bradys Lake

Brady’s Lake was created between 1952-56 as water for the Tungatinah power station on the Nive River. Bronte Lagoon flows into Brady’s Lake via a canal, with a steep gully into Brady’s Lake that is used as a whitewater slalom course. But we also caught many big Trout in the gully, as they would wait in the current for food to wash down.

There’s also a fantastic community of shacks at Bradys Lake, probably the best community of shacks in the Central Highlands. The Meaghers shack at Bradys Lake was a beauty with comfy beds, a warm fire, kitchen and a living room. We spent many weekends fishing in Brady’s Lake and Bronte Lagoon.

Tarraleah

The water from Brady’s Lake flows into Lake Binney through a canal that we could safely navigate in dads boat and we often caught a fish as we trawled through. Lake Binney also had great fishing so we’d often make our way through. Then there’s another canal in Tungatinah Lagoon, which is named after the aboriginal word for ‘shower of rain’. Tungatinah is quite shallow though, so we never fished there. After Tungatinah, the water flows into the Tarraleah Hydroelectric Power Station.

The Tarraleah Hydroelectric Power Station is located in the bottom of a spectacular ravine, with enormous Hydro pipes running down the ravine. It was so rewarding to wind down the road as my dad explained what the power station was, how it worked and what he did there. The power station was built in 1938 as part of the Derwent River scheme. It has received an Historic Engineering Marker from Engineers Australia, as part of its Engineering Heritage Recognition Program.

Tarraleah is an amazing village perched above the power station, that was first established in the 1920’s. My dad got great joy showing us the town of Tarraleah, including where he lived, the magnificent Lodge and where the golf course used to be.

The Lodge was built in the 1930’s for Engineers and Directors. In 1980 there was a population of 1600 people, 3 pubs, 2 churches, extensive workshops, sports ovals, a post office, a butcher, a police station, a supermarket, a doctor, swimming pool, golf course, cricket club, tennis courts, squash courts, a shooting club and a school. The married quarters were nicknamed Tickleberry Flat.

Once construction of the Hydroelectric station was completed, the town’s population declined and the town was closed in 1996 with the houses sold and many of them were then removed on the back of a truck. By 2005 only 5 people lived there. Then in 2005 it was purchased and renovated by Julian Homer, who created an amazing accommodation village called Tarraleah Estate.

Poatina

Poatina is another Hydro village my dad lived in and I really enjoyed going for a tour of Poatina with him. It is on the road to Arthur’s Lake, so we’d often be driving past. Poatina was built in the 1960s with 54 brick veneer houses for the workers building the Poatina Power Station.

Poatina means cave in the language of the traditional owners of the land at Poatina, the Lairmairrener, which is quite apt given the Poatina power station is housed 150 metres underground in a massive man made cavern. A 5.6km tunnel connects the power station with the Great Lake. How they constructed this masterpiece is amazing. My dad worked on the massive tunnel boring machine that helped build it.

Here’s a video that explains it all. Trust me, it’s well worth watching.

Close by, down on the farming plains is the Waddamana Canal, which is about four kilometres long, dead straight, lined with concrete, and has little weirs every ten metres. Such a fascinating little feature of the Hydroelectric Scheme and nothing like a river. We would sometimes stop and get out, just to admire the majesty. Plus there was occasionally a big Trout looking for a feed.

In 1995 the Poatina Village was acquired by Fusion Australia to provide intentional assistance to unemployed and homeless youth, through vocational rehabilitation. Which is such a worthwhile reuse of this historic village.

Poatina Road

The road from Poatina to Arthur’s Lake is a pretty incredible bendy road, as it snakes up the Great Western Tiers. Clarky, who lived next door to my grandparents, and was ever the joker, typically took his pack of dogs up in a trailer. He would joke that some of the bends were so tight that if you stuck you head out the window to spit, you’d kiss rover on the ass hahaha.

It’s a marvel how they built roads in such steep and rugged terrain. I couldn’t even imagine what it was like for the person in charge of planning and designing the road. The first time they got out in the bush to scope out the best place to build it, must have been so daunting.

Gowrie Park

Gowrie Park is a Hydro village on the North West Coast of Tasmania near Sheffield. It was constructed for the Mersey Forth power scheme, which began construction in 1963, with 2,000 people living at Gowrie Park. The Gowrie Park school catered for 250 families with many different languages spoken due to the diversity of the workers.

The Gowrie Park area has a very special connection with me for several reasons. My Dad lived there as helped build the scheme.

Gowrie Park is also on the drive up to Cradle Mountain, where my mother, sister and I bush walked so many times. Just before Gowrie Park is Claude Road. In my younger years I’d feel a really strong connection to this place as we drove through. But I never questioned it. Later in life, I was in Sheffield with my mother, and we had some time to kill before picking up my niece Sharni from school. So we grabbed a coffee and went on an adventure. She took me to where my Grandmother Verna McGee née Treloar was born in the foothills of Mount Roland, near Claude Road. Suddenly the connection made complete sense, it was where my Grandmother lived her early life.

Shacks

Shacks are very much an iconic Tasmanian tradition, that evolved from those adventurous trappers, shepherds and bush rangers building Mountain Huts. The first modern day shacks were built on Crown Land in 1944 that was leased to occupiers. They were then built all over Tasmania, mainly in isolated locations including beaches and in the Central Plateau for fishing. The high availability of Crown Land in isolated areas assisted this tradition in Tasmania.

The shacks were built for weekend getaways, and while the planning and designs had evolved from the earlier Mountain Huts, it was still quite haphazard. They are generally designed without any regard to planning or environmental concerns; the land areas were not clearly defined or of standard size; water and effluent treatment were virtually nonexistent; road and access infrastructure was poor or ill defined; owners also had no security of tenure, as they leased the land on a year-to-year basis.

The quality of the shacks also varies quite considerably, the construction techniques used for shacks were also haphazard at best, some are nice little abodes, others have been clearly slapped together without too much thought to design and using cheap materials. There were generally no plumbing, electricity, or heating. If you were lucky there would be a long drop toilet out the back, which is basically just a plank of wood with a big hole in it, over a deep hole dug into the ground. During the 1970s the shacks started to improve, and owners actually started painting them. By 2008 there were 1370 shacks on Crown Land.

We never owned a shack ourselves. We took our own shack along with us when we went fishing, i.e., the campervan, But we did know many people who had shacks at Hawley Beach, up the Lakes and many other places.

During primary school I had a good friend Matthew Payne, whose father had an awesome shack at Parramatta Creek, in the Pine Plantation. We had so much fun and games playing around in the bush building cubby houses and trying to catch rabbits.

At the Great Lake, my parents’ friend Johnny Griffiths had an awesome shack right on the lakes edge in the Breona shack community, which is in Little Lake Bay. Johnny was also an avid fisherman and I’d like to say that we caught many fish casting in from the lakes edge, but the Great Lake isn’t a great fishing lake. It was a good day’s fishing when you got a bite. It was a great day’s fishing when you actually caught a fish! Such was the reputation of the Great Lake, which is why we rarely fished there. It’s because it’s such a big lake, that the fish are scattered far and wide, so it’s hard to find them.

But there is a really nice pub at the Great Lake, and it was nice to go and get a nice meal in a warm dining room.

My brother now owns the most amazing little shack at the Great Lake. It’s a tiny little thing but it’s packed full of fun and good times.

It’s in a small little community of half a dozen shacks and he is friends with many of his neighbours. It’s up on a bit of a hill and has great views of the lake. He has taken an excavator up there and done a lot of landscaping work, both for himself and his neighbours, and this has made it so much easier to get down to the lake. It didn’t have a toilet when he bought it, so he has put in a septic tank and built a toilet inside the shack. He has done all this work himself which is impressive.

He also has a great little fire pot which keeps the shack so nice and warm during the cold days and it’s so nice just to sit back in his comfortable chairs and stare out across the lake looking for people fishing and if they’re catching any fish. They even have a wood fired oven and stove which is unusual. You don’t see many of those around these days.

The Central Plateau of Tasmania really is an amazing place, from bushwalking in World Heritage rainforest, to camping by a lake, to catching a big Trout. Also learning the amazing history of the Hydroelectric scheme from my father was fascinating and seeing all the infrastructure was magically. Everywhere you look are big towers carrying electricity lines from the power stations in the dams. They would create these giant avenues through the forest for them to run and they were straight as an arrow. One of my fathers key jobs was to build these mighty towers and they were impressive. Legend has it, that he was once dared to walk across the thin metal bars on top. He tells me he did, but I’m not too sure, as it would be an incredibly difficult to do. But they didn’t just build them on the land, some of them were in the lake as well, as the power lines crossed a bay. You had to be careful when you were fishing around them.

Then there are the dams themselves, so impressive up close, simply the scale of them towering in the landscape was impressive.

Then there were the pipes, huge pipes that ran down mountains and across plains, taking the water to where it needed to be. The most amazing ones where the ones made from wood. There was a scarcity of metal during the war years, so they got the chalk out and built wooden pipes, huge wooden pipes a couple of metres in diameter, simply amazing. However wooden pipes aren’t quite as robust as metal pipes and it wasn’t unusual for us to be driving along and up ahead theres a giant spout of water coming out of hole in them. On the plus side, the grass and trees were growing quite well around the leak.

How they constructed all of this infrastructure in the middle of nowhere, in such rugged country is simply amazing.

The Cradle Mountain infrastructure is also under constant maintenance and improvement. When I first started going, there was just a pub on the road as you went in and some tracks through the bush. Now the Cradle Mountain Lodge is refurbished and also has accomodation in cabins around the lodge. You can also fly fish in the small dam next to lodge. They’ve also installed boardwalks and seating along the trails.

The Lodge resides right at the entrance to the Cradle Mountain world heritage area. It’s still a bit of a drive into the mountain itself. When we first started going you would drive your own car, and park at Dove Lake. But it got too busy and overcrowded, so they now run buses every 15-20 minutes that stop along the way and give you a guided tour. The road in has changed as well. What was once a rutted bumpy dirt track, is now a sealed road. You can still drive in if you arrive before the shuttle buses start, but I wouldn’t want to meet a bus driving out because the road is narrow and the buses are big. Gustav Weindorfer wouldn’t recognise the place, but I’m sure he would be very impressed, because it continues to be a national park for the people, for all time. It’s even more magnificent, and even more people know about it and enjoy it very much.

The Central Highlands of Tasmania really are so impressive, for so many different reasons, thanks to so many different people. From the soaring mountains, plunging valleys, fertile plains, serene lakes, big Trout, and impressive hydroelectric infrastructure. For me, it’s all that and more, because it contains so many amazing memories of fishing and bushwalking. My father, mother, brother and sister, all learnt key skills and capabilities up in the Central Highlands, which they passed onto me. Thus the Central Highlands have a special place in my heart, just driving through it brings that special connection alive. Doing this also creates new history, with new memories, just as precious as the old memories. That’s the real beauty of history, it’s constantly being made.

Still Top Rod why is he? why is he!

The Central Highlands is such a significant location for my family, that when my dad unfortunately passed away from cancer, my brother created the most amazing memorial for him up at his shack up at the Great Lake. He needed a new gate for his shack’s driveway. So he got cracking and whipped one up in his workshop. He then let the design evolve and he decided to fancy it up by enlisted his neighbours help. His neighbour creates the most amazing metal cutouts. He found a fish cutout lying in the backyard, so it inspired him to ask him to make a man to catch the fish. Which then inspired him to dedicate it to our dad. But he then let it evolve even more and added Rob the dog, who was our dad’s favourite dog. The way he let the design evolve, makes it an even more fitting tribute to our father, because he taught us how to let designs evolve into beautiful things that you can sit back and be proud of. I am so unbelievably proud that my brother made this memorial for our father and put it in a location that meant so much to all of us. I then let the design evolve even more by buying a plaque for the gate which read “Denis McCormack still top rod” It was always a competition to be Top Rod. He was still Top Rod in our eyes. We then spread our fathers ashes at the gate.

Taking my boy fishing up the lakes

What was even more rewarding is when I finally got the chance to take my son up to the Great Lake. Both my brother and I are very excited to take Moby up the lakes, to teach him everything our father had taught us when he took us up and pay our respects at the memorial gate for his Pop.

When the day arrives, Grandma drives Moby and I up to my brother’s farm. We’ll then jump into Ashley’s Ute to head up the lakes to spend the night at his shack with him and Sharni. My sister Tracey is then going to pick Grandma up, some time after we leave and take her up to the lakes to say gday and pay respects. Although the length of the time that Grandma will wait is unknown. While it is family folklore that our Pop McGee was always early. It is family folklore that my Sister is often late. To be fair she is a very busy person, with lots of competing priorities, as she organises her family, her business, helping her husband Chris run his business and steam train hobbies. It all keeps her very busy, which means she is often very distracted and tardy. So, we weren’t in a rush.

We pack our bag into the Ute, jump in and off we go. I ask my brother to drive past Pop and Grandmas old farm, just so I can show Moby. Then as we’re driving along we point out Pops old school, and the track beside the road that Pop used to ride his horse down every day to get there. Which is story deeply etched into our family folklore. Not because of the content, but because he insisted on telling that story to everyone, all the time, over and over again.

When we reach the farm, the new owner Robbie is parked out the front. So we stop to say gday, he warmly welcomes us, then invites us in to give Moby and Sharni a guided tour of the farm on his ATV, while we sit down with his wife for a coffee. They are such nice people and it’s so nice that they proudly open their property for us. They also speak very highly of the way my grandparents helped them out when they bought the farm off them. Our extended family are regular guests and each member is warmly welcomed back into our ancestral home. Ah nutritious.

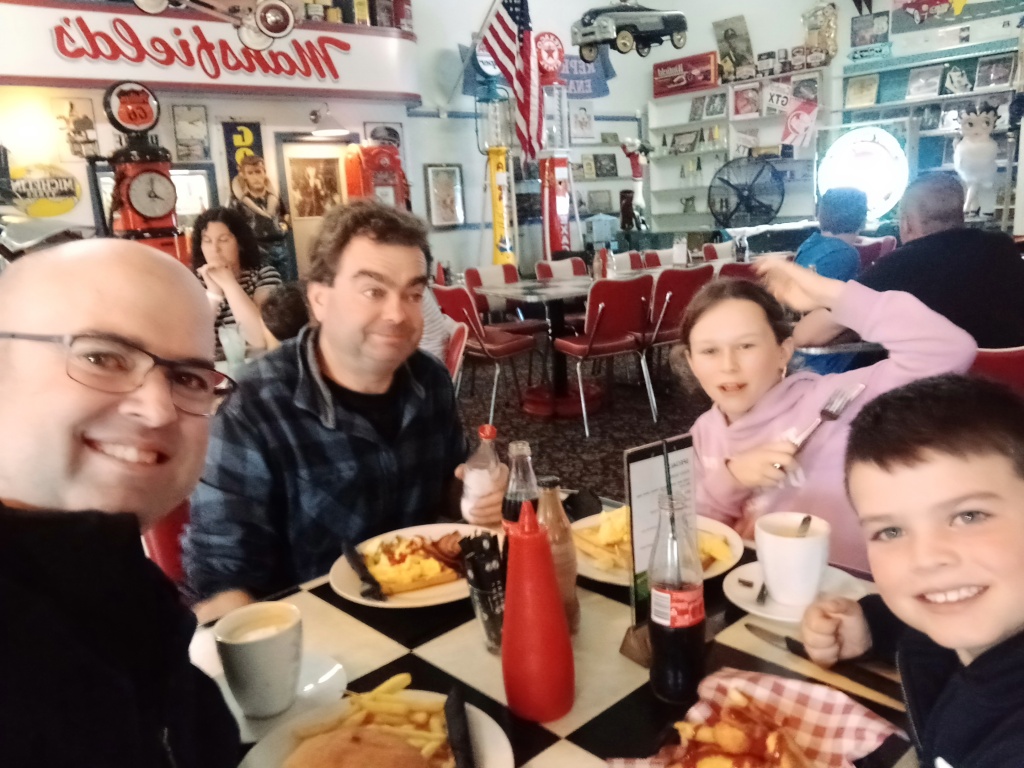

However, by the time we left, it was close to lunchtime and we were still a long way from the lakes. So we did the smart thing and stopped for lunch in Deloraine. My brother took us to the most amazing café called, Cruzin’ in the 50s Diner, that is full of racing car memorabilia and lots of other fancy stuff. Moby found a toy car that he bought with money his Nonno had given him and then he also bought one for Sharni, which was just delightful.

We then consider that perhaps we should let our Sister and Mother know that we haven’t made it up the lakes yet, and that they could meet us at the diner. So we shoot off a text message while we eat lunch and explore all the amazing memorabilia.

We finish lunch and still haven’t heard from them. Turns out they never received the text message because mobile reception up the Lakes is virtually non existent. They had beaten us up the Lakes and found a locked cold empty shack. Our sister had beaten us going up the Lakes!

Here you are witnessing the creation of a deeply etched family folklore tale that will told for generations. Trust me, we will never live this one down. It will be used in so many different contexts i.e. there’s more chance of our sister beating us up the Lakes!

At the Great Lake

The Central Plateau of Tasmania is such a significant location for our family. My father spent much of his early career building the infrastructure for the Hydroelectric Scheme. He then taught us about the history of the scheme and how to successfully catch lots of Trout. To take my little boy up there meant so much to me. To do it with his cousin Sharni meant even more. When we get to the shack we venture up the driveway to Pop’s memorial gate and bask in the memories of the man that meant so much to all of us.

We head back to the shack for Sharni and Moby to play around and they have so much fun, bending, twisting, and leaping around having pillow fights. Moby is pretty good at gymnastics, but Sharni teaches him a trick or too, she has an amazingly flexible body and balance.

We then teach Moby how to light a fire with some newspaper, and twigs. Then having some smaller pieces of wood to get the fire cranking. Building up to some logs to keep the shack nice and warm. This is a another proud family tradition.

Unfortunately the lake is a bit rough to take the boat out, but we can see birds diving into the water, so there must be some fish about. So we walk down to the lake shore with some fishing rods to try our luck. The lake shore is covered with medium sized rocks, with lots of sharp edges. Suddenly it….

Feels like I’m walkin on broken glass

We throw a couple of casts out, but don’t get a single bite. But it’s nice just to look around and talk with the kids. Moby picks up a couple of rocks he likes the look of and we wander back up to the shack so they can play around some more. He gets great delight climbing up the rock walls that Ashley had created with his excavator.

The wind eventually dies down and it looks like the rain/snow will hold off, so we decide to head out onto the Great Lake in Ashley’s boat. So we head to the boat ramp to launch the boat. This is the first time I had been fishing up the Lakes since I can’t even remember when! It definitely would have been with Pop. It bought back such good memories.

On the distant hills we can see snow flurries. We cast the lures out and trawl along the lakeshore back toward Ashley’s shack. Moby pipes up that he wants to drive and suddenly we have a new ships captain! We then cruise around the lake teaching Moby how to fish. Explaining that the best places to trawl are close to the shore, because fish like feeding on the bottom of the lake, so if you’re closer to the shore, the bottom of the lake is closer to your lure. We also explained wind lanes, where the wind blows floating bait into lanes on top of the water and by trawling through these wind lanes you’re more likely to catch fish.

Unfortunately the Great Lake lives up to its reputation and we don’t get a single bite the entire trip. We didn’t even see a fish. But at the same time it was so nice to take my little boy up the lakes to walk in his Pop’s footsteps. To learn some of the skills his Pop taught us. It was spiritually uplifting.

I have a very special connection with the Central Highlands of Tasmania. The indigenous understand this much better than I ever will, in western cultures it’s also known as a Soul Place. You know you’re there, because there’s an inner sense of calm, it feels like home and you can relax.

I think I can also thank the cancer journey I’ve been on. I’m much more aware of the interconnectedness of life. I’ve explored how people and places have shaped me and helped me to be the person I am. Understanding these relationships brings me a greater appreciation for what they have given me.